HIDDEN IN PLAIN SIGHT

THE ASTROLOGICAL SYMBOLISM OF POUSSIN'S ARCADIAN SHEPHERDS

(ET IN ARCADIA EGO)

Introduction: When we fail to understand the whole picture

In our hectic technological world of the 21 Century, we rarely stop to consider the foundations that our world is based on. We forget how the art, trade, alchemy and exploration of the Renaissance, led to the logic and experimentation of the enlightenment that ultimately formed the foundation of the Industrial Revolution. Even if we do not actively discount the earlier ideas, we view ourselves as having moved on to greater genius.

But in forgetting, we lose understanding. The base of the pyramid formed by those earlier ideas and disciplines becomes lost in the sands of time and begins to erode. In the short term that may not manifest as a problem but in the longer term we need to hold on to the earlier ideas and their relationship to the present lest we find we have lost a vital element that holds all our achievements in place.

Astrology formed a key part of a Renaissance education; a companion to Mathematics, Geography, Physics, Art and Music, yet society today, for the most part relegates it to, at best, entertainment at worst total nonsense.

Instead, to fully harness the future, we should be keeping the chain of development alive, blending the wider perspectives of the past with the precise innovation of the present.

Here we look at the impact of a failure to fully appreciate astrological symbolism in the context of art criticism. In this case, not core to the appreciation of quantum physics perhaps (!) but important as an illustration of how a field of study can lose its way.

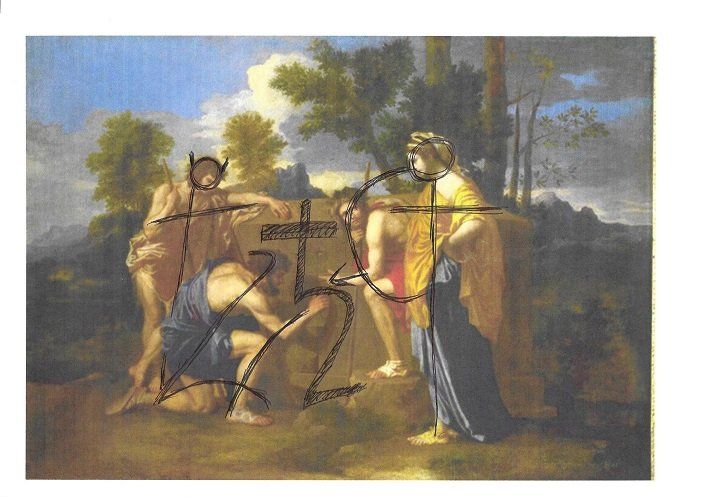

The painting

Poussin’s painting of the Acadian Shepherds in the Louvre is well known. It even made it into Dan Brown’s DaVinci Code. However, we won’t be going down that particular rabbit hole here.

The painting is basically a composition of 4 figures arranged around a tomb in a rural setting. The figures are referred to as shepherds but are wearing classical style dress. The two outer figures are standing, leaning on the tomb and one of the inner figures respectively. The two inner figures appear to be pointing, one is clearly kneeling. The kneeling figure is quite clearly focused on the tomb’s inscription “Et in Arcadia ego.”

The previous analyses

Unsurprisingly, Poussin’s painting has been much analysed. Often the analysis starts with either the initial painting of the same name (now in the Devonshire collection at Chatsworth) or the mysterious inscription which has been interpreted in a number of ways according to the exact or wider reading of the Latin.

One of the reviews of earlier analysis of the painting was conducted by Panosky (1936), who focused on the meaning of the inscription but does not spend much time on the classical figures that differentiate the painting from the artist’s earlier work. In looking at the wood, he is missing the trees.

Marin (1980) attempts to critique the painting through the lens of its geometry and what that says about the relationship between the figures depicted and through them to both the writer of the inscription and the viewer of the painting. Marin does, however, hone in on the precise position of the pointed fingers of the two central figures. Nevertheless in trying to fit the geometry and meaning to his model he misses the obvious explanation.

Both critics mention the existence of the shadow of the kneeling figure in the painting. Marin notes that the shadow forms a scythe, “the attribute of Saturn, ” but again he does not try to develop this idea more widely.

Since then, hoards of students have put forth their own theories over the decades. More recently in 2019 Aengus Dewar (The Arcadian Shepherds - Et In Arcadia Ego — aengusart) published a review of some of the past criticisms and with a fresh eye and less reverence for past experts comes close to the solution but his lack of Astrological knowledge prevents him fully unravelling the clues.

The key

By now will be clear that the key to the painting is astrological symbolism. But what I am about to present is no debateable theory or subtle reference. This key is quite simply staring us all in the face.

The figures are astrological representations of the planets/gods. And yes, there are various clues in terms of clothing and appearance. But the key is their shapes, these are quite simply representations of the symbols used for those planets:

Individually, the correlation between the stance of the figures and their symbol could be coincidental but when we take all four together we see the pattern.

Jupiter and Mars

The central pair of figures is the obvious place to start. Mars, in red of course, and with a ruddy face, is the figure that is most clearly pointing.

The symbol for Mars is defined by its arrowhead, it too points. Turn it to face the other way and we start to see the similarities.

Yet the Mars symbol is the wrong way round. So perhaps we are imagining things? Or maybe there is an aesthetic/composition reason?

So alone that would not be convincing. It is with the kneeling figure that we start to see a common thread,

Jupiter’s symbol is rather like a open number 4. The parallel here is the way Poussin has drawn the legs. Not crossed; that would be almost impossible to achieve, but the impression is there. In case we were in any doubt, the figure wears dark blue, (there may even be a hint of purple) and sports a suitably jovian beard.

We also note how the form of Jupiter fills more horizontal space than the others. Jupiter always goes big. Now when we put Mars and Jupiter together we are becoming more convinced of a pattern.

Venus and Mercury

Two standing figures would not normally suggest anything much at all. But now we are seeing the theme emerging we know what to look for. While Mars does wear a crown of leaves, we can only see it if we look closely at his head. The one on Mercury, however sticks out either side of his head. Just like the “horns” in the symbol for the planet. We see both arms, not fully outstretched, but enough to represent the crossbars on the glyph.

The figure is delicate – lacking the muscle of Mars and is dressed is a neutral colour- Mercury traditionally adapts, having no distinct colour of its own. He is also the only barefoot figure. Why would he need shoes to walk when his heels will sprout wings when he needs them?

Then we turn to Venus. Much attention has been given to the woman in the literature ( particularly as there were no females in the Devonshire picture). Her posture is the most symmetrical of all the four and has little else to distinguish it.

Once again we see both arms though, as close as artistically possible to realise the glyph, and in this case a more substantial figure as well, again very subtly mirroring the symbol.

Venus has traditionally been associated with a number of colours, Blue, green , yellow and white. Here she predominately wears blue and yellow, but she has a white cap as well. Enough clues to convince. Indeed Poussin depicts her in a similar mix of colours in Venus, Mother of Aeneas, presenting him with Arms forged by Vulcan c 1636-1637. The somewhat translucent look to Venus’s skin also seems to be a trademark look for Venus of Poussin himself cf.Venus and Mars, and Venus Mother of Adonis etc

It is clear now we have considered all four figures that the correlation between the stance of the figures and the symbols is deliberate and is confirmed by the colours of the clothing and the general appearance of the characters. But there is one final touch that makes us tip our hats to Poussin.

Saturn

The focus on death and the impression of the shadow of a scythe has already been mentioned. Yet there is another trick at play. We have found the symbols for the other 4 planets, why is Saturn not there too? But of course he is. If we shade the parts of the tomb at the front that are visible, we form a shape.

Genius. Now we know why Mars was the wrong way round, the exact positioning of Jupiter and Mars are necessary for us to see Saturn. Et in Acadia ego; he most definitely is.

So, now we understand the secret of the painting, perhaps others can turn their attention to whether the commissioner (supposedly Rospigliosi, future pope Clement IX) was aware of this little trick, and indeed perhaps requested it, or whether he remained ignorant of Poussin’s intent.

Certainly, we can all reflect on how even a little use of astrology can open our eyes to a new perspective.